This review examines the key components of photoelectrochemical (PEC) systems, including photoanodes, photocathodes, and molecular catalysts, focusing on their roles in enhancing efficiency, selectivity, and stability.

Artificial photosynthesis as a method for sustainable energy generation

Dr. Raj Shah , Michael Lotwin , Beau Eng | Koehler Instrument Company

Abstract

Artificial photosynthesis (AP) offers a potential method for sustainable energy production by mimicking natural photosynthesis to convert sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide into chemical fuels. This review examines the key components of photoelectrochemical (PEC) systems, including photoanodes, photocathodes, and molecular catalysts, focusing on their roles in enhancing efficiency, selectivity, and stability. Emerging materials such as perovskites and quantum dots are explored for their potential to improve light absorption and charge transport, while hybrid systems integrating molecular catalysts with semiconductors demonstrate advancements in reaction kinetics and product selectivity. Key challenges, including material degradation, scalability, and economic viability, are discussed, along with strategies to optimize system performance such as protective coatings, earth-abundant catalysts, and computational tools like density functional theory (DFT) and machine learning.

Introduction

One of the most prevalent challenges defining the modern day is the lack of sustainable methods for energy generation in response to the globally finite and rapidly decreasing supply of fossil fuels such as coal and natural gas. The widespread use of these materials not only harms coastal areas through their exacerbation of global warming (i.e. sea level elevation), but also pollutes air, water, and ecosystems internationally. Sustainable methods of energy generation, such as nuclear, wind, and solar, are significantly less taxing for both the environment and communities worldwide, however infrastructure to support these processes on a global scale are scarce.

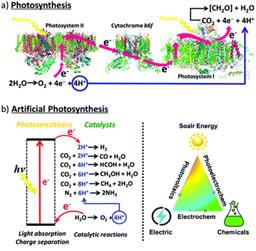

Artificial photosynthesis (AP) has been studied as a potential solution to this issue. AP is a synthetic process that mimics natural photosynthesis in plants to convert water, sunlight, and carbon dioxide into chemical energy (such as hydrogen or solar fuels) (Figure 1). This process uses photoelectrochemical cells (PECs) in two reactions. First, PECs absorb light using a photosensitizer, generating excited electrons that are transferred to an electron acceptor, while the corresponding holes are transferred to an electron donor to minimize energy loss. Then, water is oxidized into hydrogen and oxygen to generate electrons, while carbon dioxide is reduced to carbon monoxide and oxygen to replicate carbon fixation [1]. Criteria like efficiency, durability, and scalability are crucial for PEC systems to be used for AP.

Many materials have been studied for use in PEC systems. Ruthenium oxide (RuO₂) and iridium oxide (IrO₂) have been studied for their efficiency in facilitating water oxidation through the oxygen evolution reaction (OER), due to their unique electrochemical properties and high catalytic activity [2]. However, their rarity and high costs limit their use in large-scale applications. Alternatively, catalysts such as molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂), which promotes the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), are more abundant and cost-effective but suffer from lower electrical conductivity and potential degradation under prolonged light exposure in photocatalytic systems [3].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of (a) the natural photosynthetic chain in photosystems; (b) general concept of AP [24].

While advancements in catalysts such as RuO₂ and MoS₂ demonstrate progress, broader issues in efficiency and material cost hinder the large-scale adoption of AP technologies. Many photocatalytic systems do not effectively utilize the full spectrum of sunlight or degrade due to prolonged light exposure, decreasing efficiency. Others are expensive and difficult to obtain, making implementation economically challenging [4].

This paper explores recent advancements in AP research related to the efficient and sustainable generation of energy. Through an analysis of catalysts, hybrid systems, and scalability optimization methods, this review evaluates the potential of AP technologies to address global energy challenges while proposing strategies to overcome existing barriers within the field.

Photo-electrochemical cells

Design Principles

Photoelectrochemical cells (PECs) are devices that convert solar energy into chemical energy by using a working electrode composed of a semiconductor (n-type or p-type) connected externally to a counter electrode, often made of platinum for high catalytic activity. As shown in Figure 2, when light is absorbed by the semiconductor in the working electrode, electrons in the conduction band are excited to higher energy states, leaving positively charged holes in the valence band. These excited electrons are transferred through an external circuit to the counter electrode, where they participate in reduction reactions, such as the conversion of carbon dioxide (CO₂) into carbon monoxide (CO) or other carbon-based products. Simultaneously, the holes in the working electrode drive oxidation reactions, such as the splitting of water (H₂O) to produce oxygen gas (O₂) and protons (H⁺). The generated protons subsequently combine with electrons at the counter electrode to produce hydrogen gas (H₂) via the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER). An electrolyte facilitates ionic conduction between the electrodes, ensuring charge balance and completing the electrochemical circuit [5].

.png)

Figure 2. Diagram of a photoelectrochemical cell [5].

Materials for photo-electrochemical cells

PECs consist of three primary components, which significantly impact AP efficiency and performance depending on material properties. These elements are the photoanode, photocathode, and electrolyte, with optional components like separators or membranes featuring in advanced designs.

The photoanode is responsible for light absorption and initiating oxidation reactions, typically water oxidation in AP systems. Semiconductors such as titanium dioxide (TiO₂) and bismuth vanadate (BiVO₄) are commonly used due to their suitable bandgap energies and photostability. TiO₂, with its bandgap of 3.2 eV, is highly stable under UV illumination but limited in visible-light absorption. BiVO₄, with a narrower bandgap of 2.4 eV, provides better absorption in the visible spectrum but suffers from slower charge transport and recombination losses [6]. Surface modifications or co-catalysts, such as cobalt-based oxygen evolution catalysts, are often applied to these materials to enhance charge separation and reaction kinetics [7].

The photocathode facilitates reduction reactions and requires materials with high electron conductivity and catalytic activity. Silicon (Si) is commonly used due to its small bandgap (1.1 eV), allowing efficient light absorption and electron-hole pair generation. Copper-based chalcogenides, such as copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS), are also promising due to their strong visible-light absorption and excellent charge transport properties [8]. These materials are typically paired with co-catalysts, such as platinum or molybdenum sulfide (MoS₂), to improve hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) kinetics and reduce overpotentials (additional voltage beyond that required for AP), enhancing the overall efficiency of PEC systems [3].

The electrolyte serves as the ion-conducting medium, enabling charge balance between the photoanode and photocathode. Commonly used electrolytes include aqueous solutions containing redox-active species such as H₂SO₄, NaOH, or phosphate buffers, which facilitate water splitting. The electrolyte's properties—such as ionic conductivity, stability, and compatibility with electrode materials—can significantly impact the cell's performance. New designs are evaluating solid-state electrolytes and tailored ionic liquids to improve these properties under harsh conditions [9]. Optimizing the interactions among these components can allow researchers to improve PEC performance and scalability to address current AP limitations.

Performance Metrics

The efficiency and stability of PEC systems is evaluated using several metrics. Solar-to-hydrogen efficiency (STHE) is one such indicator, representing the fraction of incident solar energy converted into chemical energy in the form of hydrogen. An ideal PEC system achieves a high STH by maximizing light absorption, efficient charge carrier separation, and minimizing energy losses during catalytic reactions. For practical applications, an STHE above 10% is considered the threshold for economic viability, though most current systems measure below this benchmark due to material and design limitations [10].

Incident Photon-to-Current Efficiency (IPCE) is another relevant parameter, measuring the efficiency of converting incident photons into electrical current at specific wavelengths. This metric highlights the wavelength-dependent performance of the photoelectrode materials and their ability to utilize the solar spectrum effectively. Complementing IPCE is the photocurrent density, which quantifies the current generated per unit area under standard solar illumination. Higher photocurrent densities are indicative of superior light harvesting and efficient charge carrier dynamics. In one study, a multilayer photoanode architecture incorporating a nickel sulfide (NiS) co-catalyst achieved a photocurrent density of approximately 33.3 mA/cm² at 1.23 VRHE under standard illumination conditions, effectively doubling the performance compared to the bare structure. This improvement demonstrates the significant role of co-catalyst integration in facilitating charge separation and accelerating reaction kinetics, thereby enhancing overall PEC performance [11].

Stability is also necessary, as PECs are required to maintain performance over extended operational periods without degradation. Stability testing often involves subjecting the device to continuous illumination or cyclic operation while monitoring its photocurrent. Metrics such as the half-life of performance or the total charge passed before significant degradation are used to quantify durability. However, long-term stability remains a challenge due to catalyst poisoning and photochemical degradation, particularly in aqueous or harsh pH environments. Efforts to address these challenges include the development of more robust catalysts (which will be discussed in the following section), protective coatings, and stable electrolyte formulations to extend operational lifetimes [12].

Molecular Catalysts

Molecular catalysts extend AP functionality by enhancing H₂O oxidation and CO₂ reduction. Unlike semiconductor-based systems, these catalysts utilize coordination chemistry to enable multi-electron transfer processes with high efficiency and selectivity. Transition metal complexes, including cobalt porphyrins and manganese oxides, are notable for their ability to catalyze such processes [1]. For example, cobalt–phosphate (Co–Pi) catalysts are frequently used with PEC photoanodes to address kinetic bottlenecks in OER, offering self-healing properties and operational stability in neutral pH environments [7].

For CO₂ reduction, iron and nickel complexes have emerged as promising candidates for producing value-added products like carbon monoxide or formate under mild conditions. For instance, a nickel(II) bis(diphosphine) complex featuring a NiN₄ core has been shown to function as an efficient electrocatalyst, achieving high turnover numbers for CO₂-to-CO conversion while maintaining stability and minimizing competitive hydrogen evolution [13]. This performance highlights the potential of nickel-based catalysts to selectively facilitate CO₂ reduction while suppressing undesirable side reactions. The modularity of molecular catalysts (like the nickel complex) enables fine-tuning of their electronic and steric properties through ligand design, making them versatile tools for tailoring reaction pathways.

.jpg)

Figure 3. Schematic representation of the stages involved in achieving applicable molecular AP devices. TOF: turnover frequency; TON: turnover number. The Ru complexes shown here are highly efficient molecular WOCs [24].

To improve the scalability of AP processes, researchers are focusing on immobilizing molecular catalysts on conductive supports and incorporating them into hybrid PEC systems (observable in Figure 3). Anchoring strategies, such as covalent grafting or encapsulation within conductive frameworks, aim to improve catalyst stability and reduce degradation during operation. For instance, covalent immobilization involves forming stable bonds between catalysts and supports, enhancing durability. Electrochemical grafting, based on the reduction of aryl diazonium molecules, is a widely used method for attaching molecular catalysts onto carbon-based surfaces [14]. These approaches combine the molecular precision of catalysts with the light-harvesting capabilities of PECs to enable large-scale AP applications.

Challenges in Artificial Photosynthesis and Future Works

While AP has made significant progress since its inception, several issues must be overcome to advance its development beyond laboratory-scale demonstrations. Many of these challenges stem from material and system limitations. For instance, semiconductors commonly used in PEC cells, such as BiVO₄ and TiO₂, often suffer from low solar-to-hydrogen efficiencies due to significant charge recombination and limited visible-light absorption [15]. Additionally, while molecular catalysts provide high selectivity for reactions like CO₂ reduction, their integration into PEC systems is hindered by issues such as photodegradation and catalyst leaching during operation. These degradation pathways can reduce the efficiency and longevity of the catalysts, requiring frequent replacement or additional stabilizing modifications.

Material stability is a significant limitation for PEC cells. Photoanodes and photocathodes are susceptible to corrosion under operational conditions, particularly in aqueous environments with extreme pH levels. For instance, in dye-sensitized solar cells (DSSCs), the degradation of photovoltaic parameters has been observed over time due to environmental factors such as moisture and humidity. A study on Safranine T dye-based PEC devices reported up to a 90% reduction in performance metrics over five days when exposed to open environmental conditions [16]. Similarly, molecular catalysts, despite their tunability, face long-term durability issues. For example, cobalt-based oxygen evolution catalysts may deactivate over time due to structural rearrangements or loss of the active metal center under harsh oxidative conditions.

Another challenge lies in the economic and environmental viability of artificial photosynthesis systems. The use of rare or expensive materials, such as platinum in hydrogen evolution catalysts or iridium in oxygen evolution catalysts, greatly increases system costs [17]. Efforts to develop earth-abundant alternatives, like MoS₂ for HER or manganese oxides for OER, are ongoing but have yet to match the performance of their noble metal counterparts. Translating laboratory-scale PEC systems into large-scale devices requires cost-effective, modular designs capable of maintaining consistent performance. Issues such as electrode fouling, variability in solar flux, and long-term stability under fluctuating environmental conditions must also be addressed to enable commercial viability.

For future advancements, AP will likely depend on addressing material inefficiencies and system durabilities. Emerging materials such as perovskites and quantum dots are promising candidates for addressing such limitations by improving light absorption and charge transport. Perovskites, particularly lead-halide variants, exhibit high absorption coefficients and efficient charge separation due to their narrow band gaps. However, their instability under operational conditions, particularly with moisture and thermal exposure, has been shown to limit practical implementation [18]. Current research on perovskites focuses on compositional engineering, such as substituting lead with tin, to enhance stability by suppressing ionic transport and improving long-term operational performance [19]. Quantum dots, on the other hand, provide tunable optoelectronic properties due to quantum confinement effects, enabling broad-spectrum absorption and efficient charge transport. For example, nitrogen and sulfur co-doped carbon quantum dots (NS-CDs) integrated with TiO₂ photoanodes have demonstrated enhanced photocurrent densities, attributed to efficient hole extraction and reduced charge recombination, showcasing the significant potential of quantum dots in improving PEC performance [20].

Integrating molecular catalysts into PEC systems also remains a key focus for improving reaction efficiency. Hybrid systems that combine molecular catalysts with semiconductor materials are being developed to enhance reaction kinetics and product efficiency. Cobalt complexes immobilized on TiO₂ photoanodes, for instance, such as a trinuclear phenanthroline-linked Schiff base cobalt complex, have demonstrated significantly enhanced oxygen evolution rates, achieving three times the photoconversion efficiency of pristine TiO₂ photoanodes under simulated solar irradiation [21]. Similarly, hybrid systems coupling nickel-based molecular catalysts with BiVO₄ photoanodes have shown effective CO₂ reduction, achieving substantial production of methanol and acetic acid under visible-light photoelectrocatalysis, indicating high faradaic efficiencies [22]. These systems highlight the importance of tailoring catalyst-semiconductor interfaces to minimize recombination losses and improve reaction kinetics. However, further research into stable anchoring mechanisms, such as covalent grafting or encapsulation within conductive frameworks like metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), is critical for extending catalyst durability under operational conditions [14].

Finally, computational tools, including density functional theory (DFT) and machine learning, are being increasingly employed to accelerate material discovery and system optimization. DFT calculations, for instance, have been used to predict the electronic structures of cobalt and iron catalysts, identifying ligand modifications that reduce activation barriers for oxygen evolution and CO₂ reduction reactions [23]. Machine learning algorithms, trained on experimental and simulated datasets, are helping to determine optimal material combinations and device architectures, reducing the time and cost associated with trial-and-error approaches. These computational approaches also drive the design of tandem PEC systems, which integrate wide-bandgap and narrow-bandgap semiconductors to achieve higher solar-to-hydrogen conversion efficiencies.

Conclusion

Artificial photosynthesis offers a promising solution for sustainable energy production by converting sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide into renewable fuels. While progress has been made in developing efficient systems utilizing AP technologies, challenges such as low efficiency, material instability, and scalability significantly hinder progress. Emerging materials like perovskites and quantum dots, along with advancements in hybrid systems and computational tools, show potential for addressing these limitations. However, continued research is essential to make AP a scalable and reliable technology for renewable energy generation.

Authors

Dr. Raj Shah is a Director at Koehler Instrument Company in New York, Holtsville, NY. He is an elected Fellow by his peers at IChemE, CMI, STLE, AIC, NLGI, INSTMC, AOCS, Institute of Physics, The Energy Institute and The Royal Society of Chemistry. An ASTM Eagle award recipient, Dr. Shah recently coedited the bestseller, “Fuels and Lubricants handbook”, details of which are available at ASTM’s Long-Awaited Fuels and Lubricants Handbook 2nd Edition Now Available (https://bit.ly/3u2e6GY). He earned his doctorate in Chemical Engineering from The Pennsylvania State University and is a Fellow from The Chartered Management Institute, London. Dr. Shah is also a Chartered Scientist with the Science Council, a Chartered Petroleum Engineer with the Energy Institute and a Chartered Engineer with the Engineering council, UK. Dr. Shah was recently granted the honorific of “Eminent engineer” with Tau beta Pi, the largest engineering society in the USA. He is on the Advisory board of directors at Farmingdale university (Mechanical Technology) , Auburn Univ ( Tribology ), SUNY, Farmingdale, (Engineering Management) and State university of NY, Stony Brook ( Chemical engineering/ Material Science and engineering). An Adjunct Professor at the State University of New York, Stony Brook, in the Department of Material Science and Chemical engineering, Raj also has approximately 700 publications and has been active in the energy industry for over 3 decades. More information on Raj can be found at https://bit.ly/3QvfaLX

Contact: rshah@koehlerinstrument.com

Mr. Michael Lotwin is part of a thriving internship program at Koehler Instrument company in Holtsville, and is a student of Chemical Engineering at Stony Brook University, Long Island, NY where Dr. Shah is the chair the external advisory board of directors.

Mr. Beau Eng is a recent graduate of Stony Brook university an a researcher with Koehler instrument Company

References

[1] Machín, Abniel, et al. “Artificial Photosynthesis: Current Advancements and Future Prospects.” Biomimetics, vol. 8, no. 3, July 2023, p. 298. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomimetics8030298.

[2] Nurcan Mamaca, et al. Electrochemical activity of ruthenium and iridium based catalysts for oxygen evolution reaction, Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, Volumes 111–112, 2012, Pages 376-380, ISSN 0926-3373, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apcatb.2011.10.020.

[3] Yu, Haoxuan, et al. “The Advanced Progress of MoS2 and WS2 for Multi-Catalytic Hydrogen Evolution Reaction Systems.” Catalysts, vol. 13, no. 8, July 2023, p. 1148. https://doi.org/10.3390/catal13081148.

[4] Xu, Yi-Jun. “Promises and Challenges in Photocatalysis.” Frontiers in Catalysis, vol. 1, May 2021, https://doi.org/10.3389/fctls.2021.708319.

[5] Electrochemistry Encyclopedia -- Photoelectrochemistry of Semiconductors. knowledge.electrochem.org/encycl/art-p06-photoel.htm.

[6] Drisya, K. T., et al. “Electronic and Optical Competence of TiO2/BiVO4 Nanocomposites in the Photocatalytic Processes.” Scientific Reports, vol. 10, no. 1, Aug. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69032-9.

[7] Gil-Rostra, Jorge, et al. “Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting With ITO/WO3/BiVO4/CoPi Multishell Nanotubes Fabricated by Soft-templating in Vacuum.” arXiv.org, 21 Nov. 2022, arxiv.org/abs/2211.11558.

[8] Rahman, Md. Ferdous, et al. “A Qualitative Design and Optimization of CIGS-based Solar Cells With Sn2S3 Back Surface Field: A Plan for Achieving 21.83 % Efficiency.” Heliyon, vol. 9, no. 12, Nov. 2023, p. e22866. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e22866.

[9] Talip, Ruwaida Asyikin Abu, et al. “Ionic Liquids Roles and Perspectives in Electrolyte for Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells.” Sustainability, vol. 12, no. 18, Sept. 2020, p. 7598. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12187598.

[10] Döscher, H., et al. “Solar-to-hydrogen Efficiency: Shining Light on Photoelectrochemical Device Performance.” Energy & Environmental Science, vol. 9, no. 1, Nov. 2015, pp. 74–80. https://doi.org/10.1039/c5ee03206g.

[11] Seenivasan, Selvaraj, et al. “Multilayer Strategy for Photoelectrochemical Hydrogen Generation: New Electrode Architecture That Alleviates Multiple Bottlenecks.” Nano-Micro Letters, vol. 14, no. 1, Mar. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40820-022-00822-8.

[12] Xiao, Mu, et al. “Addressing the Stability Challenge of Photo(Electro)Catalysts Towards Solar Water Splitting.” Chemical Science, vol. 14, no. 13, Jan. 2023, pp. 3415–27. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2sc06981d.

[13] Barma, Arpita, et al. “Mononuclear Nickel(Ii) Complexes as Electrocatalysts in Hydrogen Evolution Reactions: Effects of Alkyl Side Chain Lengths.” Materials Advances, vol. 3, no. 20, Jan. 2022, pp. 7655–66. https://doi.org/10.1039/d2ma00462c.

[14] Whang, Dong Ryeol. “Immobilization of molecular catalysts for artificial photosynthesis.” Nano Convergence, vol. 7, no. 1, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40580-020-00248-1.

[15] Raub, Aini Ayunni Mohd, et al. “Advances of Nanostructured Metal Oxide as Photoanode in Photoelectrochemical (PEC) Water Splitting Application.” Heliyon, vol. 10, no. 20, Oct. 2024, p. e39079. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e39079.

[16] Maity, S., et al. “Degradation of Safranine T Dye-based Photo Electrochemical Organic Photovoltaic Devices.” Ionics, vol. 15, no. 5, Jan. 2009, pp. 615–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11581-008-0311-3.

[17] Tong, Yao, et al. “Precision Engineering of Precious Metal Catalysts for Enhanced Hydrogen Production Efficiency.” Process Safety and Environmental Protection, vol. 178, Aug. 2023, pp. 559–79. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psep.2023.08.066.

[18] Wang, Zheyan, et al. “Advances in Engineering Perovskite Oxides for Photochemical and Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting.” Applied Physics Reviews, vol. 8, no. 2, June 2021, https://doi.org/10.1063/5.0039197.

[19] Dey et al. “Substitution of Lead With Tin Suppresses Ionic Transport in Halide Perovskite Optoelectronics.” Energy & Environmental Science, vol. 17, no. 2, Nov. 2023, pp. 760–69. https://doi.org/10.1039/d3ee03772j.

[20] Li, Yueying, et al. “N, S Co-doped Carbon Quantum Dots Modified TiO2 for Efficient Hole Extraction in Photoelectrochemical Water Oxidation.” Journal of Materials Science Materials in Electronics, vol. 34, no. 24, Aug. 2023, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10854-023-11108-z.

[21] Jin, Zhaoyu, et al. “Photoanode-immobilized Molecular Cobalt-based Oxygen-evolving Complexes With Enhanced Solar-to-fuel Efficiency.” Journal of Materials Chemistry A, vol. 4, no. 29, Jan. 2016, pp. 11228–33. https://doi.org/10.1039/c6ta04607j.

[22] Silva, Ricardo Marques E., et al. “Unveiling BiVO4 Photoelectrocatalytic Potential for CO2 Reduction at Ambient Temperature.” Materials Advances, vol. 5, no. 11, Jan. 2024, pp. 4857–64. https://doi.org/10.1039/d4ma00232f.

[23] Corbin, Nathan, et al. “Heterogeneous Molecular Catalysts for Electrocatalytic CO2 Reduction.” Nano Research, vol. 12, no. 9, May 2019, pp. 2093–125. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12274-019-2403-y.

[24] Zhang, Biaobiao, and Licheng Sun. “Artificial Photosynthesis: Opportunities and Challenges of Molecular Catalysts.” Chemical Society Reviews, vol. 48, no. 7, Jan. 2019, pp. 2216–64. https://doi.org/10.1039/c8cs00897c.

The content & opinions in this article are the author’s and do not necessarily represent the views of AltEnergyMag

Comments (0)

This post does not have any comments. Be the first to leave a comment below.

Featured Product